The Biography of Malcolm X

By Harold Frost

Biography magazine, 1999

These questions came as he re-examined every aspect of his public life. “I have no idea,” he replied, an answer that suggests large possibilities for someone so young (he was 39). Perhaps, too, his answer suggests an awareness of the vagaries of fate, a knowledge that, at any moment, he might behold a man rushing toward him with a gun.

Born on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska, Malcolm Little was the fourth child of Earl and Louise Little. Omaha had a violently racist cast in those years, in common with many or most American cities. The author Stefan Kanfer writes of the city during a volatile period in the ’20s,

Since the end of the Great War, the city’s African American population had more than doubled. With the influx came resentments and racial taunts. The Omaha Bee was particularly inflammatory. The paper’s favorite topic concerned rumored assaults and rapes of white women by black men. The accused were hauled before judges and juries. When they failed to convict, another newspaper, the Mediator, warned of vigilantism in Omaha if the “respectable colored population could not purge those from the Negro community who were assaulting white girls.” (Shortly after this was written) a volatile combination of labor unrest and racial suspicion erupted. Before it ended, a black man was lynched, two other blacks died of wounds suffered during a street fight, the county courthouse lay in ruins, and the city came under federal military control.

The family moved to Lansing, Michigan, when Malcolm was 4. His father, a Baptist lay speaker and supporter of Marcus Garvey, died prematurely in 1931 when Malcolm was 6; his mother suffered a mental breakdown some years later. Malcolm says in his autobiography that his father was murdered by whites; some scholars dispute this and say the death was accidental; certainly the death can be called highly suspicious.

Malcolm kept his hopes alive, earning good grades, debating, playing basketball, and winning election to the presidency of his seventh grade class. One day when he was 14, a favorite teacher, a white man, asked him about his vocational plans. Malcolm replied that he wanted to become a lawyer. The teacher spat out a brutal response: “That’s no realistic goal for a nigger.” He told the youngster to find work that involved manual labor, such as carpentry. The lad’s fragile adolescent ego shattered like a piece of crystal hurled onto a frozen Midwestern lake. “I just gave up,” he later recalled.

Malcolm soon dropped out of school; within a couple of years he was a hustler on the East Coast, a pimp, thief, drug dealer, and playboy. He was arrested at least once. In 1946 came the reckoning – he was caught by Boston police with stolen goods, convicted, and sent up the river on a sentence of eight to 10 years.

In one of history’s endless ironies, prison saved his life. A fellow inmate whom he admired told him, “You’ve got some brains, if you’d use them,” and this simple sentence was a restorative, just as the earlier “no realistic goal” had been a devastation. Malcolm began inhaling books in the prison library, searching for clues, for sustenance, for something that would help him restore his sense of himself and escape a downward spiral of self-loathing.

Books gave him a glimpse of the world’s possibilities, and a letter from his brother Reginald gave him a path. This note, sent in 1947, described the teachings of an obscure sect called the Nation of Islam (NOI), later also known as the Black Muslims. The NOI’s doctrines bore little connection to orthodox Islam. The group said that God had come to earth in Detroit in 1930 in the form of a man named Wallace D. Fard, whose teachings were taken up by Elijah Poole, later known as Elijah Muhammad and as “the Messenger.” Among the ideas of Fard and Muhammad: God created humankind 66 trillion years ago; all humans were originally black; a black civilization ruled the earth for most of those years; whites are a race of devils created to torment blacks; and God would deliver blacks from their bondage and destroy the white devils, perhaps in the year 1984.

“My eyes came open on the spot,” Malcolm wrote of the moment when he heard this theology. He believed it – just as many people “accept on faith the parting of the Red Sea or the miracle of the loaves and fishes,” writes Peter Goldman in “The Death and Life of Malcolm X” (1973). These ideas gave Malcolm a way to understand his condition and to change his life; overnight, he developed self-respect, self-discipline, and a piety as strict as that of Puritan Massachusetts 300 years earlier. Paroled from prison in 1952, Malcolm Little took the name Malcolm X, in keeping with the belief of Elijah Muhammad that African-Americans should give up their “slave names.” The young convert was named assistant minister at a Nation of Islam temple in Detroit. He distinguished himself, and in 1954 the NOI sent him to the nation’s largest black community – Harlem, in New York City.

In the 1950s, as the civil rights movement gathered momentum in the American South, some blacks in the big cities of the North felt disconnected from it. Not only was the movement taking place many hundreds of miles away, it seemed entirely too polite, churchly, forgiving, and integrationist. Malcolm X, by contrast, was right there in Harlem, and a fair number of blacks accepted him as one of their own – a man with first-hand knowledge of the streets. He was not at all forgiving. He was angry.

A tall, lanky, commanding, charismatic figure, Malcolm spoke extemporaneously and brilliantly, sometimes for hours, using the ideas of the Black Muslim faith as a foundation, firing off sweeping riffs about the condition of African Americans, about how whites had contributed to that condition, about what he regarded as the fraudulent promises of integration and Christianity, and about the need for blacks to get enraged, get energized, get organized, stake claims to their own land, feel pride in their blackness, and make it clear that they were prepared to defend themselves.

White America didn’t know what to make of this. The idea of black rage was new in the 1950s – the “Sambo” myth of black docility was still current, promulgated in studies of the antebellum South by a racially-biased white historian named Ulrich B. Phillips, finding wide circulation in college textbooks.

As whites learned about Malcolm X they accused him of teaching hate. “The Hate That Hate Produced” was the title of a 1959 TV documentary on the NOI prominently featuring Malcolm. Biographer Goldman spots something more subtle: “Malcolm didn’t teach hate, or need to; he exploited a vein of hate that was there already.”

Malcolm said that all white people are devils and enemies. The extent to which he believed this racist doctrine is unclear – he was unfailingly civil in private conversation with whites – but he said it often from his podium and from street corners, and he seemed to be speaking from his heart. He won cheers. The scholar James H. Cone, in his book “Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare?” (1991), writes about a street crowd listening to Malcolm: “(They responded) enthusiastically with shouts of ‘Right on!’ and ‘Teach, Brother Malcolm, teach!’ as he whipped them into a seemingly uncontrollable frenzy.”

Frenzy could be a tonic, Malcolm observed, and perhaps could begin the process of changing lives.

But by the early 1960s he had questions about his faith and its senior leadership. Some whites, he saw, were worthy of respect – for example, certain students that he met on the college lecture circuit, and Mike Handler, who covered the Nation of Islam for the New York Times. Also, Malcolm and other Black Muslims became concerned about excesses and lapses in the NOI leadership – the alleged extramarital affairs of Elijah Muhammad, which Malcolm investigated personally, as well as the cultism that surrounded the Messenger. Meanwhile the NOI’s leaders grew jealous of Malcolm’s fame and influence.

By the late autumn of 1963 Malcolm and Elijah Muhammad were actively hostile toward each other, and on March 8, 1964, Malcolm announced that he was leaving the NOI to form a new black nationalist party that would, he said, heighten the political consciousness of its members. The Black Muslim leadership was furious at the departure of the sect’s most charismatic leader. “Such a man as Malcolm is worthy of death,” wrote Minister Louis X, known later as Louis Farrakhan. These words appeared in an NOI newspaper and percolated down through the ranks; Farrakhan, says historian Clayborne Carson, “was one of those in the Nation (of Islam) responsible for the climate of vilification that resulted in Malcolm X’s assassination.”

Malcolm knew he was a marked man. He told a journalist that the Nation of Islam “can’t afford to let me live….I know where the bodies are buried.”

He embarked in 1964 on the remarkable last year of his life, a journey of self-discovery that could have come from the pages of Joseph Campbell. He disenthralled himself from the creed of his earlier years and committed himself to trusting the authority of his senses. He demonstrated in vivid terms that people can change, that new things do shine under the sun, and that the beliefs and certainties of one’s youth – and the mistakes – need not rule one’s mature soul, can be supplanted by ideas that hold more truth and resonance. He saw that he could achieve not merely the ego-boosting adoration of the crowd but the quieter heroism of openness, with its attendant (and scary) vulnerability.

Seeking better answers to his questions about life, America, race, revolution, and God, Malcolm explored mainstream Islam, Pan-Africanism, anti-colonialism, and socialism. He spent many weeks in Africa conversing with revolutionary leaders. He made a pilgrimage to the Middle East and wrote in the New York Times that many white Muslims he met there showed him kinship. He still felt distinctly edgy toward white America – whites in the U.S. were enemies of blacks, he said, until their behavior proved otherwise – but he began to talk less about anger and more about how racism could conceivably be reduced. In the spring of ’64 he was photographed shaking hands with Martin Luther King Jr., an event that never would have happened a couple of years earlier.

He became an accredited minister of Sunni Islam, and he began using a new name, El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. He worked with the heightened energy of a man who sensed an early death. And then it came.

On February 21, 1965, as he spoke to 400 people at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, several men jumped up out of the audience, rushed toward him, and shot him to death. He was 39 years old. Three Black Muslims were convicted for the assassination and received life sentences.

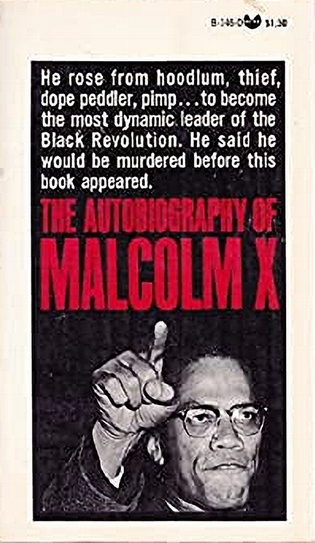

Malcolm X achieved significant international fame in his lifetime – his assassination was Page One news. He became an icon in death. Late 1965 saw publication of “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” an intensely readable book co-authored with Alex Haley (who wrote “Roots” in the 1970s). Early paperback editions of the autobiography had a riveting cover photograph: Malcolm speaking with the full passion and wrath of a prophet, his right hand raised, his finger pointing upward, his face brooking no interference. That face was splashed across paperback stands in drugstores nationwide and thoroughly shocked segments of white America. (It must be added that the book is sanitized, downplaying the stark fact of Malcolm’s radical politics.)

With his book, and his life, Malcolm X, writes James H. Cone, made a signal contribution to “the way black people thought about themselves,” helping them find a way out of self-hatred via black pride. He was a primary progenitor of the black consciousness movement that flowered in the ’60s and continues today, affecting “the whole of black life,” writes Cone, including art, education, politics, and religion. (Martin Luther King had a far greater impact than Malcolm X on politics and legislation, and on the fabric of the nation; as historian Garry Wills says, “More than any single person [King] changed the way Americans lived with each other in the sixties.”)

If he had lived, would Malcolm X have continued to evolve? Would he have shaken off the anti-Semitism that he still carried, and the sexism? Would he have become an integrationist in some form, willing to acknowledge and embrace American pluralism? The questions are tantalizing. The final answer came in the form of bullets. ●

Update 2011: The best biography of Malcolm X is “Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention” by Manning Marable (2011).